Automating creativity: Will AI replace artists?

In the spring and summer of 2022, the internet was suddenly inundated with a stream of strange, fascinating images. A giant lobster playing basketball; a court sketch of Godzilla on trial; Darth Vader ice fishing. It started to feel like reality was dissolving slightly, but in a good way.

Of course, the internet has always been awash with compelling or confounding images. The very concept of virality, still so dear to digital marketers, has never really escaped its association with surreal and uncanny visuals, from “Hide the Pain Harold” to “dat boi”.

But this was something different. These images were often highly detailed, sometimes even beautiful. They used a range of styles, from oil painting to collage and black-and-white photography, in bizarre or unexpected ways. Many of them looked like the work of experienced designers or artists, but their sheer profusion and variety made that hard to imagine.

In fact, these images were the startling output of a handful of newly launched AI text-to-image generators. Seemingly from nowhere, a number of pioneering companies had found a way to turn short text prompts into fascinating, attention-grabbing images – and people were letting their imaginations run wild.

But amidst all the excitement and hilarity, there were calls for caution. It was immediately apparent that these image generators, however fun they might be to play around with, had potentially seismic social implications.

Most of all, they raised the age-old spectre of human irrelevance. After all, what use are graphic designers or digital artists if AI models are now capable of generating powerful images across an endless array of styles, all in a matter of seconds? And visually focused creatives aren’t the only ones at risk. The same advanced AI that powers text-to-image generators is also being used to produce engaging, high-quality written content from simple prompts, suggesting that copywriters might also be an endangered species.

Despite the threats these tools seem to pose, we can hardly justify simply refusing to engage with them. AI generators have the potential to radically streamline the routine, instrumental aspects of creative work, leaving more time for ideation and experimentation, and it’s hard to see even the most ardent technophobe turning that down.

In this post, we’ll take a closer look at how these recent developments in AI play into a variety of wide-ranging social and ethical debates that purpose-led agencies can’t afford to ignore. Of course, we’ll also try to answer the question that’s probably foremost in your mind: are the machines coming for my job, too?

Raging against the machine: A brief history of robot uprisings

The fear that robots will replace us has a long history. In fact, it’s at least as old as the word “robot” itself. The term was coined by the Russian writer Karel Čapek in 1920, for a play in which artificial beings (the roboti) rise up against their human masters and ultimately wipe them out. An inauspicious debut, needless to say. By 1927, cinema had followed Čapek’s lead: Fritz Lang’s early sci-fi masterpiece Metropolis features a robot that leads a violent rebellion and is ultimately burned at the stake.

Lang’s disturbing vision became the blueprint for much dystopian sci-fi of the subsequent decades, but the fears that Metropolis conjures now seem a bit dated. Over the past half-century, the vision of a mechanical humanoid hunting down its inventors has been gradually replaced by something more insidious and disturbing. Rather than fretting at the prospect of being physically overpowered by robots, we have become preoccupied with the threat of artificial intelligence – that is, with a machine that threatens us not because it’s stronger than us, but because it’s smarter.

This shift is best represented by two classics of 80s sci-fi cinema: James Cameron’s The Terminator and Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner. While the former is best remembered for Arnold Schwarzenegger’s iconic turn as the titular cyborg, the film’s true antagonist is the mysterious Skynet, an AI defence network that becomes self-aware and tries to exterminate humanity. In Blade Runner, meanwhile, the androids hunted by Harrison Ford’s eponymous assassin pose little physical threat – Ford’s character is able to dispatch them with relative ease. What is truly dangerous is their capacity to replicate human behaviour so successfully that they are almost impossible to distinguish from actual humans. Hence their name within the film: they are not robots but replicants.

It’s not always easy to persuade people that films have much to tell us about the state of the world, or that we can use pop cultural trends to diagnose fundamental social shifts. But in reality, there are few better places to look if you want to understand how public sentiment has changed. After all, it’s hardly a major leap to suppose that a culture awash with apocalyptic images might have some concerns about its long-term future.

So what does our fascination with technology turning against us tell us about the collective anxieties of our hyper-digital age?

While the possibility of a full-blown climate collapse may have moved from the realm of the disaster movie into the evening news – and from there to the 3 am doomscroll – the prospect of sentient AI subjecting humanity to its iron rule is still largely confined to fiction. (Notwithstanding the Google engineer who recently claimed the company’s LAMBDA chatbot was sentient, shortly before being fired.)

But this does not mean that AI does not pose a significant – even existential – threat to human society, at least the way it’s currently organised. It just means that this threat is less about marauding hordes of cyborgs and more about wholesale changes to how we live and work. The AI researcher Ajeya Cotra recently suggested there is a 35% chance of “transformative AI” by 2036 – that is, AI “powerful enough to bring us into a new, qualitatively different future” with an impact comparable to the industrial revolution.

The persistent fascination with artificial forms of humanity, from robots to replicants to Skynet, is easier to understand if we forget about the spectacle of armageddon. While the Terminator might be well-suited to the silver screen, the threat posed by AI is far from fictional.

Move slow and break things: Are we all Luddites now?

Would you call yourself a Luddite?

If you’re a digital marketer, probably not. After all, in contemporary usage, a Luddite is a technophobe, someone who proudly professes ignorance or incompetence when it comes to the latest tech trends. Someone who still uses a flip phone, for example, or who doesn’t really see the point of having a smart speaker.

Needless to say, if your role hinges on helping brands stay at the forefront of digital innovations, this is generally not a good look.

But this current usage is actually something of an injustice to the Luddites themselves, who were far from anti-tech reactionaries. In reality, the Luddites were a group of English textile workers who waged a campaign against the introduction of automated machinery in the early nineteenth century. They did this not because they were opposed to new technologies, but because they wanted to defend their way of life.

And their concerns are pretty easy to understand. These were skilled, experienced workers who faced the loss of their livelihoods as factory owners began to realise that automation would let them get more output from fewer workers. The fact that this would lead to mass unemployment and a decline in the quality of the products was seen as an unfortunate but excusable side-effect.

Subsequent history has seen the realisation of many of the Luddites’ fears. Skilled manual workers have borne the brunt of increasing automation over the past two centuries. From the car factories of Detroit to the steelmakers of Sheffield, increasingly sophisticated machinery and robotics have allowed companies to downsize their operations without any loss of productivity, leading to waves of mass unemployment and regional decline.

But it turns out that it wasn’t just manual workers who should have been worrying about what automation might lead to. The last three decades have seen the tide slowly turn against white-collar “knowledge workers”, whose relative job security has begun to seem like just a temporary reprieve.

For much of this period, the emphasis has mostly been on automating the more mundane aspects of knowledge work – using spreadsheets to rapidly process data or automating communications with customers, for example. As a result, it was possible to believe that automation would actually help knowledge workers flourish rather than simply replace them. Spending less time on routine, repetitive tasks would leave more time for “higher order” cognitive work – and who wouldn’t want that?

Nevertheless, the promise that automation will allow people to focus on more complex strategic and creative work did not prevent growing anxieties over the future of white-collar work, especially as AI began to show significant advances. It turns out that Mark Zuckerberg’s famous injunction to “move fast and break things” is a lot less exciting when you’re the one getting broken.

In the past five years, a plethora of articles and reports have begun to ask whether AI will spell the end for a wide range of jobs that were previously thought to be too complex or too creative to be taken out of human hands. With titles like “There will be plenty of jobs in the future: You just won’t be able to do them” and “Are the robots coming for white-collar jobs?”, the mood was obviously becoming more fretful. Inevitably, the COVID-19 pandemic made matters worse. A 2021 survey by PwC found that 60% of workers worry that automation would put their job at risk, and 39% expect their job to be obsolete in five years.

There were still, of course, those who persisted in singling out specific skills as “automation-proof”, trying to identify a few islands still safe from the rising tide of AI. Kevin Roose, a New York Times columnist and author of the encouragingly titled Futureproof, maintained in an interview with New York Magazine that “creative” work would be harder to automate. One of his recommendations was that workers should start figuring out how to “make it clear that you are a human creating human work”.

Naturally, the interview was titled “How to Ensure the Robots Won’t Come for Your Job”.

A year later, the idea that creative work would be AI-proof sounds quaint. The headlines moved quickly from denial to bargaining and acceptance. In August, the New York Times plaintively demanded that “We Need to Talk about How Good AI is Getting”. Tellingly, the article was almost entirely focused on AI image generators and copywriting tools, with just the briefest nod to its scientific implications. Meanwhile, New York Magazine published its own follow-up piece on AI, written by the magazine’s photo editor. It was focused on the wittily-named DALL-E image generator, and the title sounded actively panic-stricken: “Will DALL-E the AI Artist Take My Job?”

Maybe we all become Luddites when it’s our livelihoods on the line – when it’s clear that something will get broken, and it’s either us or the machines.

The future is now: AI’s golden decade

Digital marketers are no strangers to automation. From ad targeting to reminder emails and content optimisation, there is a wide range of tasks that are now routinely made more manageable by leveraging automated solutions.

If this has yet to lead to a mass panic about our impending unemployability, this is because these tasks still require extensive human guidance and oversight – the automated part is, in reality, a fairly minor aspect of the overall process. While a given social media platform may offer automated ways to target specific user groups and manage your ad spend, the work of building ads and evaluating campaigns is still firmly in the hands of humans.

And despite the increasingly important role of data in digital marketing, there has remained a substantial creative component. From branding and design to copywriting and video production, many key marketing tasks have been seen as fundamentally resistant to automation. If you were looking to safeguard your future from the robot reckoning, it seemed like there were few safer places to be.

Until now.

The past six months have felt like a quantum leap in the effectiveness of AI for creative tasks. And while this is the product of a long and arduous process going on behind the scenes in laboratories and universities – the past ten years have been called a “golden decade” in AI research – the immediate effect is like being shown a particularly convincing magic trick.

While much of the current focus is on AI text-to-image generation, it was actually AI copywriting that experienced the first major leap forward, thanks to the 2020 release of OpenAI’s GPT-3 language model. Trained on 570GB of text – including the entirety of Wikipedia – GPT-3 is now being used to power writing software capable of turning a short prompt into a substantial piece of content.

However impressive this might be, it cannot compare to the sheer impact of DALL-E 2, which entered its open beta phase in July this year. Also developed by OpenAI, DALL-E 2 combined GPT-3’s ability to interpret text-based prompts with a model called CLIP, which was trained on 400 million image-text pairs. This enormous dataset allowed the model to consistently connect words and phrases with corresponding images and, through a complex process called diffusion, generate new images from text-based prompts.

The results were nothing short of astounding. Those lucky enough to get early access to DALL-E 2 quickly started filling their social feeds with strange, hilarious, baffling images. Some even asked their followers to suggest prompts themselves. The same month saw a different, equally eye-opening AI text-to-image generator called Midjourney launch its own open beta phase. The sense that a major shift was underway was difficult to ignore.

A portrait of the artist as a robot

It was immediately clear that DALL-E 2 and Midjourney were more than just fuel for the latest social media fad. In late June, just prior to its public beta release, the artist Karen X Cheng used DALL-E 2 to produce a cover for Cosmopolitan magazine.

Six weeks later, the tech journalist Charlie Warzel used Midjourney to generate images for an opinion piece for The Atlantic – a piece that had nothing to do with AI. Only the small, easily overlooked captions revealed that the accompanying images were AI-generated.

In a LinkedIn post, Cheng reflected on her experience of working with DALL-E 2 and sounded a comforting note for any anxious creatives. She stressed that “a TON of human involvement and decision making” went into producing the cover, rather than it being a question of “typing in a few words and BAM magically you have the perfect image”. While she acknowledged that “the natural reaction is to fear that AI will replace human artists”, for her part she began to see DALL-E 2 as less of a replacement and more a “tool for humans to use – an instrument to play”.

Warzel’s experience was rather different. In an apologetic follow-up to his Atlantic piece, he acknowledged that his use of Midjourney had generated a significant backlash. Many artists and creators saw Warzel’s use of AI as effectively taking paying work away from hard-pressed professionals. Others worried it would justify publications cutting back on their art budget.

The debate reached a new level of urgency in early September, when an image generated by Midjourney won a prize at the Colorado State Fair fine arts competition. Understandably, many artists were vocally critical of the decision, while the artist himself was accused of misleading the judges. Though he had been explicit that the work was created using Midjourney, he had not explained to the judges what this actually meant in practice. As a result, they may not have grasped just how much of the work Midjourney was responsible for.

Amid these anxieties about job security and arguments about craft and skill, it starts to feel like we haven’t come so far from the Luddites smashing mechanised looms. But AI doesn’t just reignite centuries-old debates about the risks our inventions pose. It also adds its own set of ethical issues – some of which have no precedent at all.

Did we just automate copyright infringement?

From its very inception, the internet has been unsettling widespread assumptions about creative work, especially when it comes to the issue of ownership. The late 90s saw the eruption of a major (and still unresolved) battle over copyright, as broadband internet connections and standardised file formats allowed for widespread filesharing – or piracy, as the film and music industries were at pains to call it.

Two decades later, it remains the case that any artwork that finds its way online becomes very difficult to control. The ease of copying and reproducing images still poses major problems for artists, who often struggle to avoid their work being stolen and used by others without attribution or credit, never mind remuneration.

The success of AI text-to-image generators is, on the one hand, a consequence of this proliferation of images on the web. As we mentioned above, the AI behind these tools needs to be “trained” by processing millions or even billions of images. And where do these images come from? The internet, of course.

While OpenAI has not revealed details of the dataset it used to train DALL-E 2, one of its competitors, the open-source Stable Diffusion, is more transparent. Its owner, Stability AI, has stated that the model was trained using a dataset of 5.85 billion image-text pairs assembled by the non-profit organisation LAION – an organisation partly funded by Stability AI.

This enormous dataset was assembled by “scraping” billions of web pages and indexing any images alongside the alt-text describing them. An analysis of parts of the dataset used to train Stable Diffusion found that a significant number of the images came from sites like Pinterest, which allows users to upload images with very little oversight, as well as stock image websites like Shutterstock.

As a result, the dataset is rife with copyrighted images by prominent artists. There are at least two major issues that result from this, both with significant ethical and legal implications.

In the first case, it’s important to remember that the AI is only able to generate new images by synthesising the images it has been trained on. There are debates over what this means for whether AI can be genuinely creative – proponents argue that this kind of elaborate synthesis is effectively no different from what human artists do. But what is inarguable is that Stable Diffusion is using the creative work of thousands – perhaps millions – of artists to power its seemingly magical creative capacities. And it’s doing so without asking permission, never mind offering compensation.

The second issue is even more problematic. The fact that the AI has been trained on images generated by human artists – many of whom are still living – allows it to actually imitate the style of those artists. If the artist’s work features extensively in the dataset, it can do so with astonishing accuracy. Prominent artists like Simon Stålenhag and Greg Rutowski have found that their work is easily aped by an AI generator, much to their chagrin. From this perspective, DALL-E’s much-vaunted creativity turns out to be, as a Bloomberg article puts it, closer to “plagiarism by machine.”

These issues add further nuance to the anxieties of artists and other creatives outlined above. It’s one thing to have a sophisticated robot take your job; finding out that it can do so because it studied your work without permission is quite another.

But offering novel ways to automate copyright infringement isn’t the only unexpected downside of AI generators.

All too human: On algorithmic bias

While AI image generators raise a number of unique ethical issues, they also exacerbate some existing problems. As AI and other forms of automation have increasingly found their way into our daily lives in the hope that they will simplify a wide range of everyday tasks, it’s become apparent that there are some major risks.

For instance, it turns out that, rather than helping us to avoid subjective biases, AI can serve to entrench them. The term “algorithmic bias” was coined to capture the way that automated processes can effectively encode human prejudices, making them even harder to tackle.

Tools like DALL-E 2 and Midjourney make this issue very apparent – in fact, they’re basically a handy visual explainer. In DALL-E 2’s lengthy documentation, you can find a section called “Bias and representation”, which illustrates the problem. It provides ten different results for the prompt “a builder”, and another ten for the prompt “a flight attendant”. The former shows exclusively white men, while the latter are all East Asian women. The results for “nurse” and “CEO” show similarly problematic assumptions.

This is not a case of bias being deliberately built into the software by designers who are themselves biased. Rather, it’s a side-effect of how the models are trained. If a dataset contains far more images of male CEOs than female CEOs, then the AI will associate the term “CEO” with images of men. As a result, it will usually generate images of men when asked for CEOs.

Of course, from a narrowly statistical standpoint, there simply are more male CEOs than female ones, and the dataset exemplifies this fact. But this isn’t the result of some natural, inherent connection between maleness and leadership. It’s the outcome of long-standing biases and barriers that have conspired to prevent women from attaining positions of power in the business world (and in most other places). And this includes the reinforcing effect of representation, in which the lack of readily available images of female CEOs serves to discourage women from following that particular career path. As the phrase goes, you can’t be what you can’t see.

Ultimately, if AI models internalise this bias, they will contribute to reinforcing it – alongside the many other biases that the dataset will inevitably reflect.

It’s fairly easy to imagine the consequences of this kind of algorithmic bias if companies do actually end up gutting their art departments in favour of AI generators. At best, we’re likely to see a continuation of the unequal representation that already plagues stock image repositories. At worst, the removal of another layer of curation – of the kind that experienced designers or art editors can provide – will lead to a flood of biased imagery. While Shutterstock and Getty are eagerly trying to encourage diversity in stock photography, mass adoption of AI generators threatens to undermine this progress.

This debate around diversity and representation is by no means the only major ethical dilemma that AI generators are finding themselves caught up in. The ongoing struggles over harmful content on the web – from violent imagery to political misinformation – have also become a lot more pressing. After all, DALL-E 2’s training dataset also contains innumerable images of famous people, allowing it to generate “deepfakes” of celebrities and politicians with minimal technical knowledge or input from users.

To their credit, the developers of the AI models are not unaware of these complex issues. The makers of DALL-E 2 not only highlight them directly, but they have also restricted access to the software so that they can moderate and filter how it’s used. They try, as far as they can, to prevent the generation of violent imagery, deepfakes, and other problematic content.

Others, however, have eschewed this approach. In August, Stability AI launched its Stable Diffusion image generator as an open-source product, enabling anyone to build on or modify its code. As a result, though the model released by Stability AI did include some minor content filters, these can be circumvented. In principle, people can use Stable Diffusion to make whatever images they like, with all the risks this implies.

The company’s founder seemed rather unconcerned about the implications, telling The Verge: “Ultimately, it’s peoples’ responsibility as to whether they are ethical, moral, and legal in how they operate this technology.” This controversial approach has not proved offputting for investors – the company achieved a $1bn valuation in a recent funding round.

The most important question: Can AI write this article for me?

The ethical, moral and social implications of AI generators are only just beginning to be explored. Part of what makes these tools so exciting – and so disturbing – is that they seem to have burst into our lives before we’ve had the chance to really reflect on their consequences. We’re trying to negotiate with this enormous change in real-time, for better or worse.

For us as marketers, that means we can’t escape the question of how we should be using these tools – or if we should be using them at all.

While each of us will have our own ways of navigating the ethical dilemmas that AI generators raise, one question that we can valuably pose is: are they actually useful? That is, can they support – or even replace – the work of content writers or designers?

Well, the best way to explore this question is to simply try it out. Could the tools that generated so much media attention and artistic anxiety over the past few months have actually helped me to write this article? Could they have even taken over for me entirely?

To begin with, I took the opening paragraph of this section and asked an AI text generator called SudoWrite to continue it for me. Here’s what it came up with:

“There is a case to be made that we as marketers are these tools’ biggest burden right now. They are being used to create content for us, for free. It is frustrating for us to see someone else getting credit for something that you know was partly your work. But the day that we can generate content better than a bot, we were wrong to rely on them in the first place. It’s important to remember that there is a difference between “via a bot” and “by a bot”. As a marketer, you should provide quality information and let the technology do the rest.

Complicated rules around this are developing on a week by week basis, and it’s important to keep your eyes open and be ready to adapt to new policies as they emerge and shift. First, remember that whether we like it or not, bots are here to stay. So now we have to be careful to be not just compliant with the latest changes, but insightful, too.”

Now personally, I don’t see this as a big win for AI. In fact, I’m struggling to understand what it’s actually saying. I can sort of follow the gist of it, but it’s hardly a resounding success. (And those missing hyphens in week-by-week are a worry, too.)

But maybe I’ve been a bit unfair. The prompt I gave SudoWrite was relatively complicated and by no means a summary of what I’m trying to say. So, I tried again, with the following prompt:

“AI has taken a major leap forward in the past decade. As a result, the prospect of it taking over creative roles like design, branding and copywriting is becoming more likely. But is AI technology truly able to replace humans when it comes to complex creative tasks?”

SudoWrite offered the following as a continuation:

“Research suggests that AI technology is, in fact, capable of carrying out complex creative tasks. One study found that AI was able to come up with new designs for cars that were both stylish and aerodynamic. Another study found that AI was able to create novel brand names that were both memorable and meaningful.

So it seems that AI technology is well on its way to taking over many creative roles from humans. However, there are still some areas where AI falls short. For example, when it comes to copywriting, AI often struggles to come up with original ideas and tends to produce dull and uninspiring work. It also often fails to capture the nuances of human emotion and so its work can seem cold and robotic.

Overall, though, the evidence suggests that AI technology is well on its way to becoming a powerful force in the world of creativity. So it looks like we may need to start getting used to the idea of robots taking over our jobs!”

Now we’re talking. The text is clear, focused on the topic, and even offers some references to external studies (though it doesn’t cite its sources). From a technical standpoint, there’s nothing much wrong with it.

Unfortunately, from a creative standpoint, it’s got less to recommend it. There’s nothing particularly arresting or insightful about the points it’s making – indeed, it is a bit “dull and uninspiring”. As a simple digest of the way people currently write about AI, it’s acceptable – even useful. As a piece of content designed to grab a reader’s attention and offer them something they couldn’t get elsewhere, it’s far less effective.

SudoWrite does have a lot of added functionality that I could use to tweak what it offers me, and it can quickly generate multiple different suggestions for me to choose from. On that basis, you might accuse me of being unfair – maybe I’m just trying to save my own skin?

But I would object (of course) that we shouldn’t move the goalposts here. Given the pervasive worries about the replaceability of creative workers, I shouldn’t have to get too involved. The more I’m required to exercise my judgment and creative input, the less work that AI is actually doing. Beyond a certain point, it’s no longer worthwhile to spend hours tweaking the prompts and evaluating the results when I could simply write the thing myself.

Illustrating the point

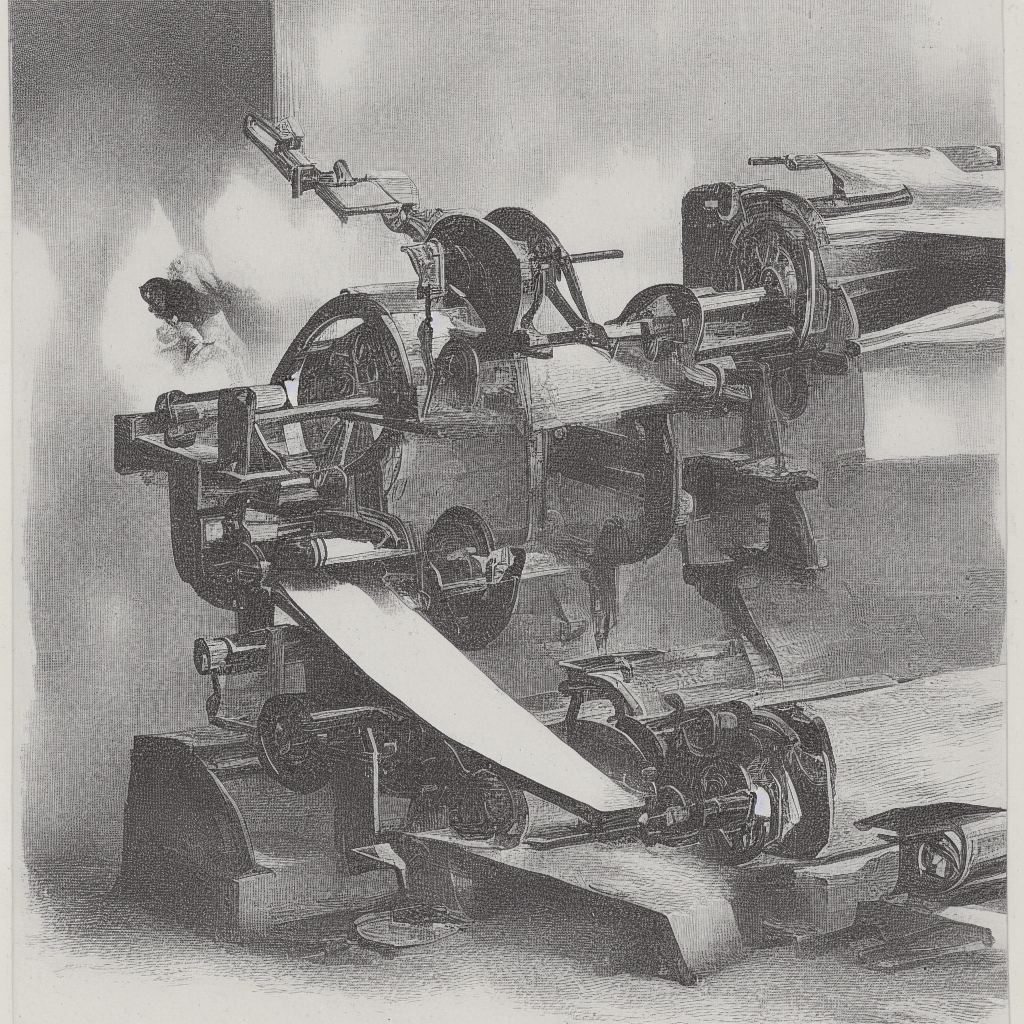

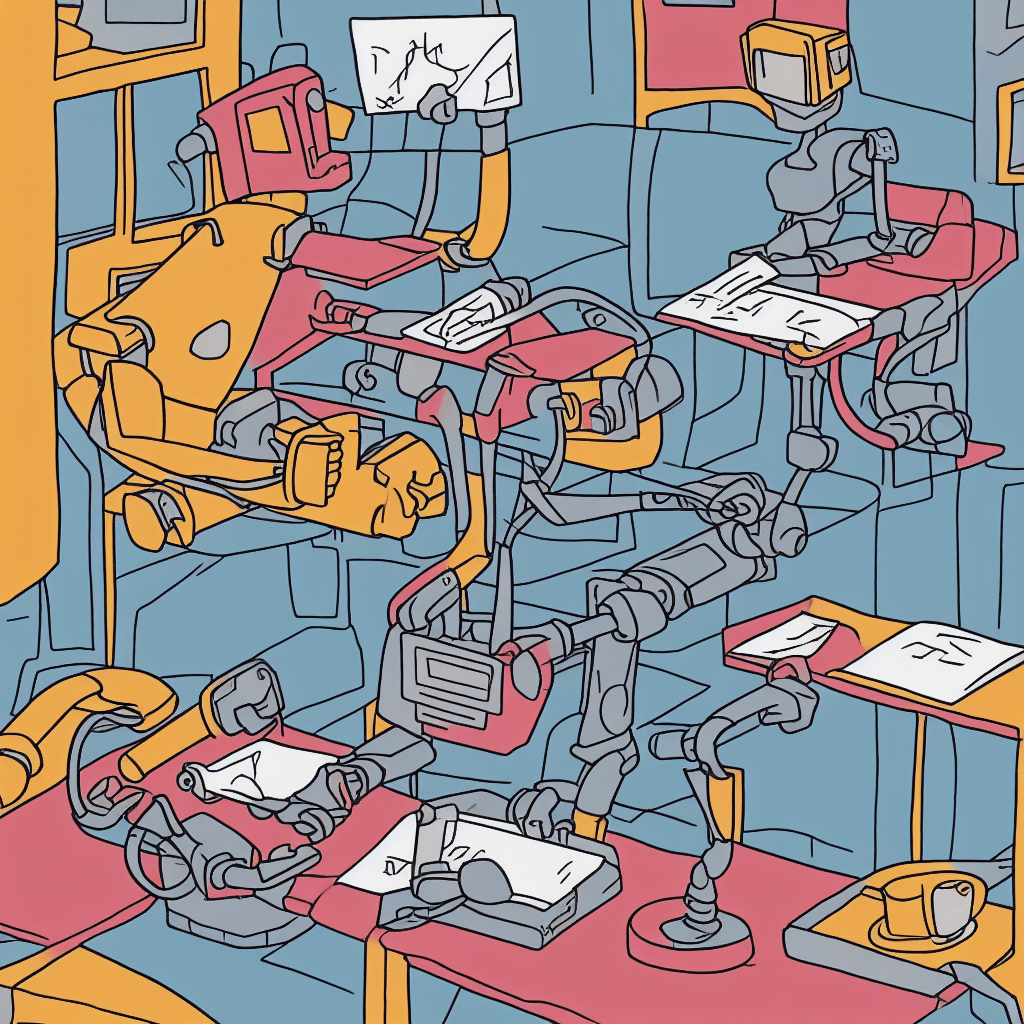

So much for copywriting. What about images? After all, that’s the focus of the furore. Could I use an AI text-to-image generator like DALL-E 2 to illustrate this post instead of turning to stock photographs or Castle’s Branding & Design department?

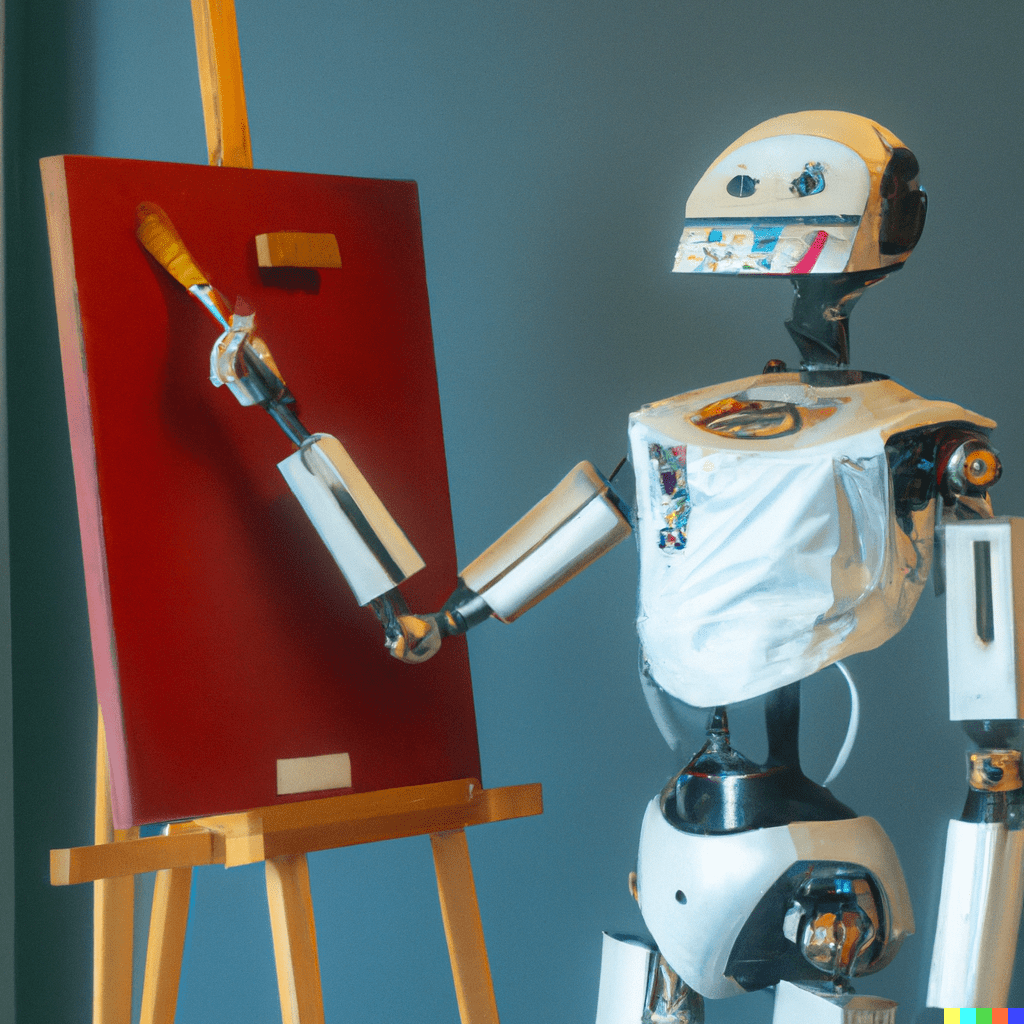

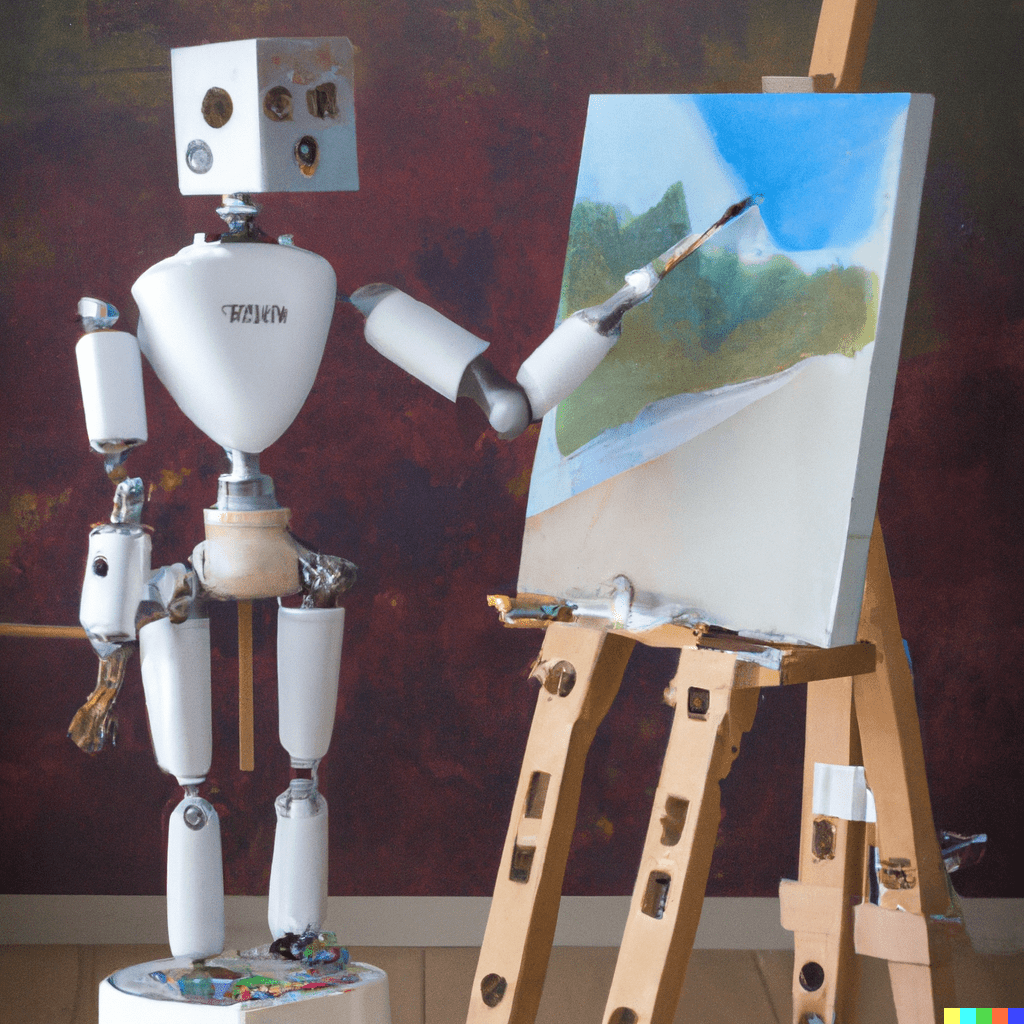

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the results that DALL-E 2 offers are more immediately impressive – even startlingly so. In the first case, I decided to come up with my own concept for how I’d illustrate this piece. I’m no designer, so it was a fairly simple concept: a robot painting on an easel. DALL-E 2 offered me four options, of which I thought two were quite striking:

They’re by no means perfect, of course. The faces are a little odd, and only one of the two is actually painting something. But there remains something undeniably magical about being able to generate these images from just a basic idea in a matter of seconds – especially for someone with no artistic skill to speak of.

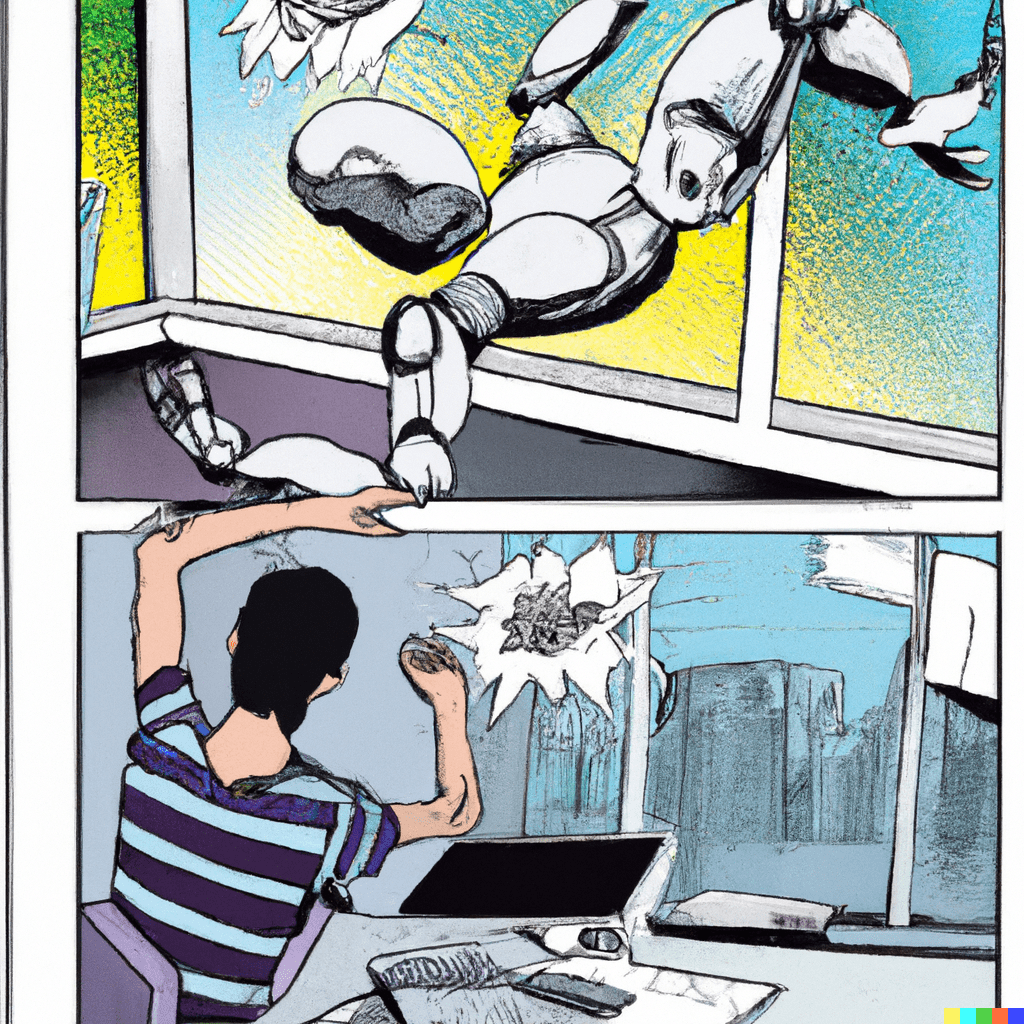

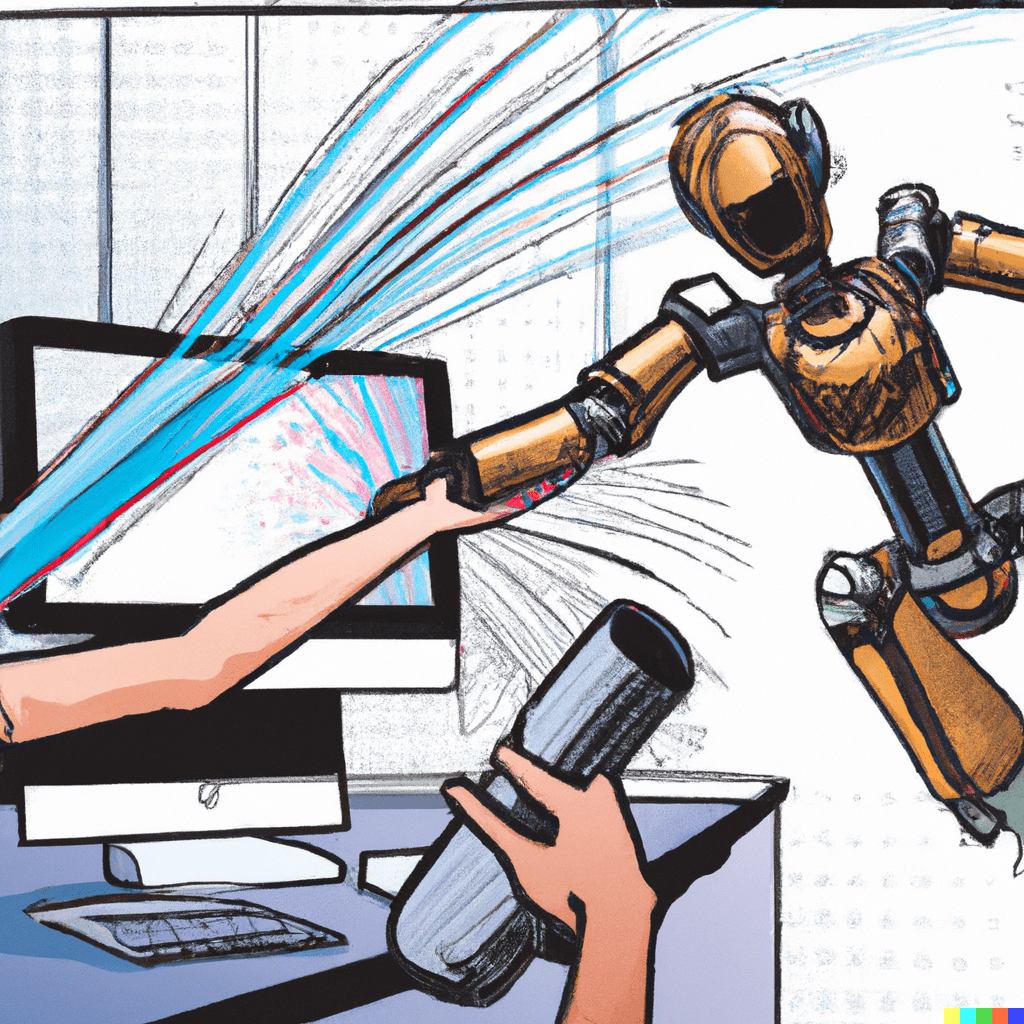

I decided to ask Castle’s Head of Creative, Pete Richardson, if he had a prompt he thought could be used to illustrate the piece. He offered a more on-the-nose alternative: a robot attacking a graphic designer in a comic strip style. Again, the results were undoubtedly impressive.

But still, there are drawbacks. DALL-E seems to struggle with composition – the different elements of the image aren’t always logically arranged. Human figures can make this apparent: limbs sometimes end up in the wrong place, and facial expressions can be a bit confusing.

All of these issues can be mitigated, to a degree. Detailed and well-phrased prompts tend to produce better images – or at least images that more fully reflect your intentions. Indeed, there are already people offering their services as experts in this area, describing themselves as “prompt engineers”. DALL-E also allows you to generate new images using an existing image as a model, which can help to refine your outputs further.

But this all starts to look a lot like work – the kind of work that AI was supposed to replace.

So, am I out of a job?

This is the important question of course. But thankfully, the answer seems to be a resounding “no”. Even these simple experiments with AI generators show that the prospect of mass redundancies in creative departments is still remote.

Most obviously, both SudoWrite and DALL-E relied on a prompt that I had to provide. Not only were some prompts better than others at guiding the AI to a worthwhile outcome, but the actual concept behind the prompt had to come from a human. SudoWrite cannot generate an article about the impact of AI on creatives without being asked to do so, and DALL-E can’t illustrate the piece without someone imagining how you might best visually represent that topic.

Once the generator has done its work, there’s a whole other step of evaluating what it’s come up with. Content writers and graphic designers have painstakingly accumulated the experience required to look at an image or a piece of writing and say whether it works or not. They know when a sentence doesn’t have quite the right rhythm, or if a paragraph loses its thread halfway through; they know when the colour palette is just slightly too dark, or if the underlying concept isn’t coming through clearly.

At present, even the most sophisticated AI tools can’t generate ideas of their own. Nor can they reflect on their own work and make improvements. This means that they lack two of the fundamental skills for creative work, especially in a marketing context. Whether you’re looking to write an engaging blog on an exciting industry trend or you need an eye-catching illustration for a landing page, the process of ideation and iteration – of inventing and reflecting – is where you truly generate value. That’s where the ineffable, never-ending process of creative work really takes place. And it’s a place where, as yet, AI cannot go.

This does not mean these tools are useless – quite the opposite. Some parts of the writing and design process really are repetitive and rote. Sometimes you get stuck and need a helping hand – how do I start the next sentence? Where do I go from here? In cases like these, AI generators can be enormously helpful. They can act as spurs for your creative work or even as handy shortcuts from time to time. But in both cases, you already need to know where you’re going, and to be able to recognise when you’ve arrived. And these are things that only humans can do. (For now, at least.)

Ultimately, new technologies have always disrupted creative work, and have usually caused no small degree of panic as a result. As a recent Axios article notes, it’s worth remembering that photography did not eradicate painting, and cinema hasn’t replaced theatre – but they did force them to evolve. What AI means for the future of writing and design, both in marketing and more broadly, is an open question. But fears of mass redundancy fail to do justice to the truly transformative potential of these new tools.

(Oh, and just for full disclosure: All the accompanying images in this blog were generated by Stable Diffusion and DALL-E 2. Pretty cool, right? But take a closer look and you can probably see they’re far from perfect.)